Intestine of the Sooty Song Sparrow

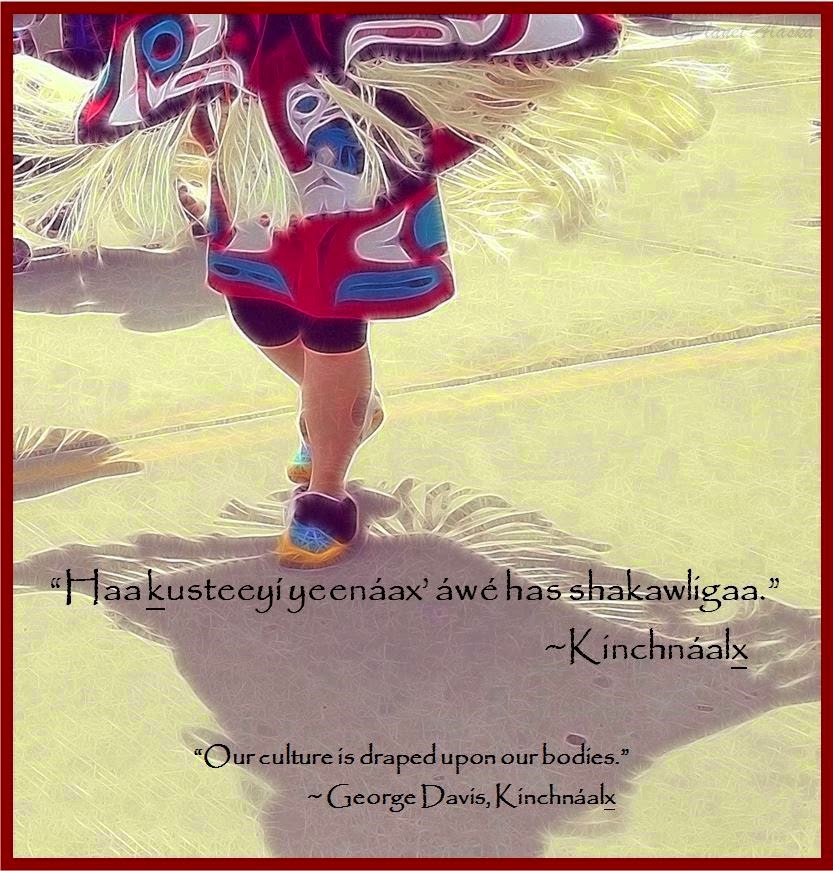

My daughter dances to the drummer’s beat. Draped around her back is a black button robe trimmed in red and dotted with abalone buttons that form a pattern. She turns her back to the audience and the wool robe moves with her. The fabric ripples and the black-legged kittiwake on her back flies to the mountain with grief in its beak.

“We wear our histories,” is a common Tlingit saying. Tlingit weaver and clan sister, Teri Rofkar, advised me that we should be telling stories about what’s happening right now. I apply the weaver’s advice to my writing and mentoring. I work with indigenous writers, among them the Tlingit, an Alaskan Native tribe in Southeast Alaska. My children are Tlingit and I’m adopted into the T’akdeintaan clan, Snail House. My Tlingit name is Yéilk Tlaa Mother-of-Cute-Little-Raven.

|

| (c)Teri Rofkar |

Rofkar weaves contemporary stories into her dance robes. The three types of dance robes, the Chilkat, Raven’s tail, and button blanket, are complex designs with many threads, stitches, buttons, and patterns. The robes tell stories. Rofkar’s earthquake robe depicts the 1964 Alaskan earthquake, which she experienced as a child. Another robe tells of the history of our clan family in Lituya Bay.

I live in Sitka, Alaska and belong to a multi-cultural writers group, consisting mostly of women. (Blue Canoe Writers). We are weavers of words and stories. Sometimes we weave our stories together; sometimes we help one another discover patterns and words for the things we have difficulty expressing. In a traditionally matrilineal culture such as the Tlingit’s, life is complicated by the male-dominated American culture. This complexity is sometimes hard to describe. We get frustrated. We get angry. We write. My daughter, a poet, writes about the male clan leaders who are on the sex offender list. Her poem questions this non-traditional practice.

As a person with indigenous ancestry myself, I understand the complexities of language death, assimilation, acculturation, and how women’s roles are effected by change. Those changes create the basis for our stories. Sometimes it’s hard to look at the now, especially when the Tlingits have been in southeast Alaska for ten thousand years. Life here is greatly influenced by the past and traditions.

I explain to my fellow writers that what you experienced when you went to the grocery store is just as important as what your ancestors experienced in their day-to-day living. You know the story of how Raven brought daylight to mankind, but the story of the time when you couch-surfed through ten years of your life is just as important. Look for patterns. Weave your story.

The stories and poems written from our lives are intricate just like the dance robes, and, like the robes, our words must dance to live, to tell our stories to the next generation. As women writers we try to figure out how life makes sense. We imagine the things that haunt us, that make us laugh, and make us cry. We search for words. We look for patterns: the teeth of the killer whale, leaves of fireweed, intestine of the sooty song-sparrow. By telling our stories we make a pattern for others to follow. We weave a new future.

My daughter writes a poem. It is her clan’s story of first contact in Lituya Bay. She sets the pen down and picks up the poem; its wool is heavy with words and ink. The patterns she’s designed herself: the teeth of men, the curling sails of a sailing ship, the song of her clan women. She drapes the poem along her shoulders. The cadence of her words, its drumbeat. The letters flutter like the black strands of wool hanging from the robe. She moves through the verses like the sailing ship heading into the bay. She holds a hollow plant up to her eye and looks through it so as not to turn to stone. This is the moment when her story changes, the moment when her elders head out to the ship, the moment when she feels the poem, heavy on her shoulders. This is the moment when her clan women will listen to her words and remember their todays as well as their histories and look forward to their future. This is when she dances.

*This blogpost was previously published on another blog: The Better Bombshell.

Comments